Photos from The Prime Ministers, reprinted with permission from The Toby Press. Photo: Jono David

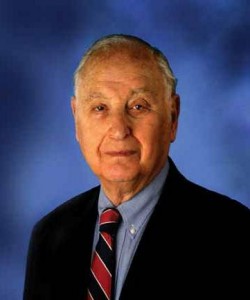

Sitting in his private office in Jerusalem, Yehuda Avner still carries himself like a polished diplomat. The former ambassador and adviser to Israeli prime ministers is an energetic eighty-two year old, and has retained the gracious manner and self-deprecating humor that undoubtedly served him well throughout his years of service to the Jewish people.

Working alongside towering figures such as Menachem Begin and Golda Meir, the religiously observant Avner was intimately involved in Israel’s statecraft for three decades, taking part in policy meetings and sitting in on talks with heads of state. He took assiduous and detailed notes throughout, in the process compiling a treasure trove of material on the contours and course of decision-making in the Jewish state. The result is The Prime Ministers, an Intimate Narrative of Israeli Leadership (Toby Press, 2010), Avner’s lucid and crisply written account of many of modern Israel’s struggles and triumphs.

Unlike almost any book published before it, Avner’s volume provides the reader with an authentic feeling of being a “fly on the wall” as Israel’s leaders wage war and seek peace. It is rife with anecdotes that prompt laughter and occasionally move one to tears, while offering extensive insight into Israel’s history and diplomacy. In an interview with journalist Michael Freund, Ambassador Avner shared some recollections from his illustrious career.

Jewish Action: Who is the most admirable political figure you have known and why?

Yehuda Avner: I would say that from the point of view of affection, admiration and emotional attachment, my answer without a doubt has to be Menachem Begin. I joined the Israel Foreign Service in the late 1950s, and was soon seconded from the Foreign Ministry to the Prime Minister’s Bureau where I worked for a whole galaxy of Labor, socialist, secular, agnostic prime ministers—Levi Eshkol, Golda Meir, and Yitzhak Rabin. When Menachem Begin ultimately entered office in 1977, I, being an observant Jew, was ecstatic to find myself working for a leader who, in my eyes, seemed to represent the quintessential Jew.

Begin came from a totally religious background, from Brisk. He was a real “Yid.” While not perhaps totally observant in his private life, one reason being that his wife, Aliza, was hardly religious, in public life he was strictly observant— Shabbat, kashrut, everything. Among his many guises as commander of the Irgun when the British were hunting him with a price on his head, he invariably assumed the role of a yeshivah bachur or rabbi.

JA: As an observant Jew, you must have faced situations in which there was a conflict between your religious obligations and the demands of your job. How did you deal with this?

YA: Occasionally I did find myself in conflict on matters between religious conscience and the duties I had to perform. In such situations I consulted with the late Chief Rabbi Shlomo Goren who was chief chaplain to the IDF when I first entered the Foreign Ministry, and was familiar from his own army experience with tasks a diplomat is often required to do, such as decoding urgent cables on Shabbat and so forth. He espoused what is known as the famous Clausewitz Law, which states that war is an extension of diplomacy by other means. In other words, successful diplomacy can prevent war and, therefore, falls into the category of pikuach nefesh, saving lives. This being so, when potentially threatening circumstances required me to break Shabbat, Rabbi Goren ruled that I was obligated to do so even in situations in which there appeared to be no immediate and present danger.

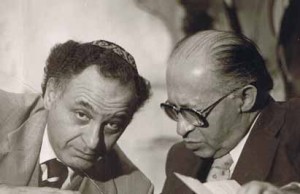

Yehuda Avner consulting with Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin, 1977.

JA: Did Rabbi Goren impose certain restrictions on how to go about violating Shabbat even in cases where it was deemed necessary?

YA: Yes, he certainly did. Rabbi Goren was emphatic that one must uphold the principle of shinui, of doing whatever one was doing with a difference, so as to remind one that it is Shabbat. So, for example, if I had to write something on Shabbat, which wasn’t very often, I would do so with my left hand. Or if I had to be driven somewhere to attend a meeting that had life and death implications, I used to sit on the car floor. This certainly ensured I would not forget it was Shabbat. Indeed, there were times when doing something toch shinui, in a manner so very different from the norm, reinforced my awareness of the sanctity of the day.

JA:Were there times when your adherence to religious principles got you into hot water?

YA: Yes there were. I recall an occasion in 1975 when US Secretary of State Henry Kissinger was engaged in shuttle diplomacy, negotiating with Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin and Egyptian President Anwar Sadat in an attempt to bring about an interim agreement in Sinai. The negotiations broke down because Rabin was not satisfied with proposals which impinged on Israel’s security. Kissinger went off in a huff, readying to place the failure of his mission on Israel. This showdown occurred just before Shabbat and Rabin asked me to immediately prepare our case for worldwide broadcast before Kissinger had a chance to brief the pressmen accompanying him on his flight back to Washington. A battle for public opinion was on, not least to win over Congress and the American public at large to accept our version of things, and I was the only one on the premier’s staff who was not only familiar with all the facts but also had the language competence to promptly make our case. But I told Rabin that Shabbat was upon us, and what he was asking me to do was not a matter of vital policy but of hasbarah (public diplomacy or advocacy), and for that I was not willing to violate Shabbat. Well, do I remember the look of contempt on his face as I left.

The next day, Shabbat afternoon, after davening Minchah at the Gra shul in the neighborhood of Shaarei Chessed, I happened upon Rabbi Shlomo Zalman Auerbach. He knew what I was engaged in, and he asked me in Yiddish what was new. I told him what had happened, and he said to me in Hebrew, “Are you sure you had all the information to make the right decision?” I took this to mean that I might not have made the right decision after all, and immediately started to walk back to the prime minister’s office. When I got there it was already Motzaei Shabbat. Rabin was in the midst of an emergency Cabinet session, and as I walked in, he spat at me, “Now you come? It’s too late,” and he showed me the briefing that Kissinger had given the journalists accompanying him on his flight back to Washington, in which he placed all the blame for the crisis on Israel’s shoulders. This had the most serious consequences. President Gerald Ford declared a reassessment of the whole Israeli-US relationship, beginning with a partial arms embargo. To this day I do not know if I did the right thing, and whether following Rabin’s instructions would have made a difference or not.

JA: You traveled with the prime ministers on their trips abroad. Was kashrut ever an issue?

YA: All the time! Until Begin, no prime minister of Israel bothered about kashrut, whether at home or abroad. Once, when we were returning from a trip abroad, I tried to explain to Rabin what an educational impact it would have on the local Jews if they knew that wherever the prime minister of Israel appeared at official functions he was sure to be observing kashrut. But Rabin simply did not understand me. Reared, as he was, in a totally secular environment, it was beyond his grasp. “There’s no need,” he said. “I don’t want to bother the White House about such matters.”

When Begin entered office in 1977, he made it obligatory that all official functions be kosher, and his hosts, in whatever country we visited, were happy to oblige.

Yehuda Avner, Prime Minister Menachem Begin, and UN Secretary-General Kurt Waldheim discuss Lebanese border tensions, July 22, 1977.

JA: Reading your book, regardless of the political ideology of the prime ministers involved, each one comes across as someone infused with idealism and dedication to the country. Is that a thing of our past? Why don’t we have leaders of a similar caliber today, or do we and we just don’t see that side of them as much?

YA: I’ve given lots of thought to this. Times have changed; people have changed. The likes of a Ben-Gurion or an Eshkol or a Golda or a Begin were all shaped by the turbulent times through which they lived, beginning with the turmoil of the Eastern Europe of their youth. It was in that furnace that they were forged. Our new generation of prime ministers, beginning with Bibi Netanyahu and Ehud Barak, was born into a more individualistic and more materialistic Israel. Neither of these men was hewn from the same flinty rock as their predecessors. But that does not make them any less patriotic as their predecessors.

JA: So will we ever have another Begin?

YA: God-forbid the new generation of leaders will have to go through the kinds of trials and tribulations that confronted the previous ones. The previous ones were revolutionaries— the pioneers who, against all odds, literally changed the course of Jewish history by establishing the Jewish State. In the process, a man like Menachem Begin spent much of the earlier years of his life constantly on the brink of life and death. He had no Israeli army to defend him or come to his rescue. So the Begin we came to know as prime minister was a product of the Begin we knew as a hunted outlaw, the Begin of the Gulag, the Begin forever haunted by the Holocaust. So no, I don’t think we shall have another Begin. But always we shall have prime ministers leading an abnormal nation in an abnormal land, for that is the nature of our country and people, as foreseen in the Torah—“Am l’vadad yishkon, A people that dwells alone.”

JA: If he were alive today and serving as prime minister, how do you think Begin would deal with Iran’s threats to Israel and its drive to build nuclear weapons?

YA: Begin had a doctrine which said— one: If an enemy of our people says he seeks to destroy us, believe him. And two: Israel will never allow an enemy of our people to manufacture weapons of mass destruction against us. Iran fits that bill totally, and Begin would act accordingly. Exactly how I cannot presume to know, but believing as he did in a God of Israel, and haunted as he was by the Holocaust, and driven by the vow that he would never allow such a catastrophe ever to happen again, I can imagine that his policies, overt and covert, would be aggressively focused to make it plain to the West that if it doesn’t act, Israel, in one shape or another, would.

JA: What do you make of Israel’s hasbarah efforts these days and the seeming inability to get our message across?

YA: When you look back, you see we had no hasbarah problem prior to the 1967 Six-Day War. Then we were viewed as the little David standing up to the Arab Goliath.

Now, of course, it is the other way round. However, and you might be surprised to hear this: in my view our hasbarah has been eminently successful on the strategic level. Because where hasbarah really matters is on Capitol Hill and in other Washington corridors of power. And there, if you look at the record, you see Israel has enjoyed a fairly consistent record of bipartisan support and strategic cooperation. It is on the tactical level of daily news coverage and our inability to fill the TV screens with brilliant spokespeople of the caliber of an Abba Eban that we are failing badly. After all, where do most people derive their information if not from television? And television largely deals in images, not facts. Our public diplomacy people have not done a good job in branding Israel as a country that truly is democratic, enlightened, and brimming with brilliant entrepreneurship.

JA: One of the most remarkable things about your book is that one can read it and still not know precisely what your own political views are.

YA: In my book I seek to be the fly on the wall.

President Jimmy Carter and Prime Minister Menachem Begin, May 1, 1978. Ambassador Avner is in the white jacket on the bottom right, taking notes.

JA:Why is it that so few religious people go into the Foreign Service?

YA: Let me first say that in the government generally religious people are represented more than they were before, not least in the highest echelons of the IDF. However, the Foreign Service can be a difficult arena for a religious person to work in simply because the chances are that for much of the time he can find himself, and his family, in what we call a hardship posting, meaning somewhere in the Third World, an underdeveloped country, where there is no Jewish community or infrastructure to lead a Jewish life. And after all, most of the world is Third World. Indeed, at an early point in my own career I was a candidate for a posting to Burma, and in preparation for it I actually began learning how to slaughter fowl for Shabbat meals. But I was never sent there because at the last minute the prime minister of the day, Levi Eshkol, needed someone with a strong command of English, and I was selected for the job.

JA: You served as a diplomat in Washington. What do you think the future holds for American Jewry?

YA: There is a law in physics that quantity makes quality, so I have no doubt that given the size of the American Jewish community, its future is not in doubt. However, the quality of much of American Jewish life is in such decline due to intermarriage and assimilation that the engine for its longevity and passion is undoubtedly Orthodox. Orthodoxy is based not only upon ritual practice, but equally upon Judaic scholarship, and both are tragically lacking in the other denominations where, too often, rabbis are more buddies of their congregants than their challenging leaders, and where the mantra of “tikkun olam” has become a palliative for Judaism. Tikkun Olam is a beautiful concept but it is not Judaism per se. It is central to it—“l’takein olam b’malchut Shakkai”—but the humanistic interpretation of it has deprived it of much of its authentic Jewish relevance. On the positive side, there is more Jewish education today in America than there has ever been before, which illustrates my thought that the two most important words in the whole of Tanach are “v’shinantam l’vanechah—Teach [the words of Torah] to your children.”

Michael Freund served as deputy director of communications under Israeli Prime Minister Binyamin Netanyahu during his previous term of office. He is the founder and chairman of Shavei Israel, a Jerusalem-based group that assists “lost Jews” seeking to return to the Jewish people.