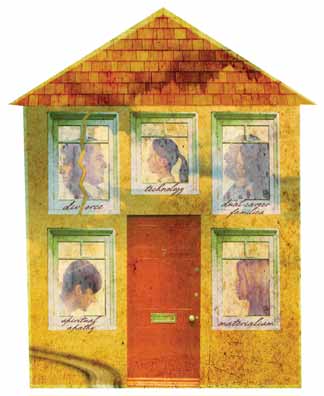

Jewish Action posed a number of questions to leading rabbis and mental-health professionals about the various challenges facing the contemporary Orthodox family. Contributors were asked to select one or two questions of their choice to respond to. This accounts for the unevenness of the responses. Many of the contributors chose to answer the question on divorce which in and of itself is indicative of the topic’s significance.

While statistics are not available, it seems that there is a dramatic increase in divorce in the Orthodox community, particularly among young people. Why do you think this is so? What can be done?

Rabbi Dr. Harvey Belovski

It is easy to blame the zeitgeist for the growing divorce problem. We inhabit a responsibility-adverse, “throw-away” society, one which discourages people from dedicating themselves to long-term relationships and from remaining committed to them when problems arise. And while increased acceptance of divorce has its positive sides, it also deters couples from working on their marriages when the going gets tough. Combined with a predominantly casual attitude toward sexuality and palpable scorn for stable, “boring” monogamy, contemporary society offers a toxic milieu within which it is challenging to maintain even robust marriages.

Yet over-focusing on the influence of secular mores prevents us from identifying and addressing causes of marital discord that originate from within the Orthodox world.

There are positive aspects of the “shidduch system,” yet its misuses contribute to poor relationships and early breakups. Unfortunately, some parents seem to view a shidduch not only as an attempt to find a lasting, happy match for their offspring, but also as an opportunity for social and economic advancement. Often in collusion with their children, they judge a potential mate based on genealogical, financial and even sartorial or other superficial criteria, instead of focusing on core qualities such as stability, personal happiness, commitment-capability, honesty and character refinement. While of course everyone pays lip-service to the importance of these qualities, in reality they are commonly overlooked in favor of a “good catch”—a shidduch that meets the approval of their peers. The solution is obvious, but hard to implement as it involves a paradigm shift at a number of levels. Educating our young people about real relationships would be a good start.

Furthermore, many couples date too few times prior to getting engaged. Most people cannot make a competent decision about whether they wish to share every aspect of their lives with a prospective spouse without spending extended periods together in a variety of settings. People and their lives are complex; “unpacking” them takes time and cannot be rushed. Yet social expectations and pressure from parents or shadchanim may drive a young couple to decide quickly, frequently leaving a whole raft of issues undiscussed, personality traits unexplored and behavior-patterns undiscovered—all “time-bombs” that can, and sadly often do, detonate later on and destroy the marriage. And while I understand the genuine religious and other concerns that motivate the desire to “get it over with quickly,” they must be resisted if we are to prevent many quite unnecessary breakdowns and their attendant long-term misery.

And speaking of potential “time-bombs,” numerous young people plunge into marriage despite unresolved emotional, sexual, familial and religious hang-ups. Some are cognizant of these issues but date anyway because of social pressures. Others imagine that marriage will solve their problems; yet others are blissfully unaware of them even though they may be painfully evident to others. This is a recipe for disaster, since inevitably these issues will surface and destructively affect the marriage. And even if the union survives, it is certain to be rocky and challenging. Again, the solution is obvious: sort out your problems before getting married and remember that while singlehood can be painful, being trapped in a bad marriage is always worse. Marriage never solves these problems. Yet the stigma associated with mental health and other personal problems and the pressure felt by parents to get their children “married off” young often prevail.

Other causes of divorce not confined to the Orthodox community yet prevalent within it include: poor communication; lack of those who “role-model” functional, happy relationships; unwelcome family pressure to conform or perform; absurd expectations in terms of personal happiness and finances. The latter is especially acute in those parts of the community where couples expect to marry young, have large families, live in an expensive middle-class neighborhood and pay crippling tuitions, yet remain students well beyond marriage with often weak earning-potential. These pressures can destroy even the healthiest relationships.

Rabbi Dr. Harvey Belovski is the rabbi of the Golders Green Synagogue in London. He earned a PhD from the University of London on the topic of Chassidic hermeneutics, and is the author of several books.

To hear an interview with Rabbi Belovski, please visit Savitsky Talks at http://www.ou.org/life/relationships/dating/why-are-more-orthodox-couples-getting-divorced/. Savitsky Talks is a weekly twenty-minute audio program exploring topics in Jewish Action and other topics in contemporary Jewish life.

Dr. Aviva Biberfeld

There was a time when young people learned how to conduct themselves in a marriage by observing their parents and other positive role models. However, the increase in familial dysfunction due to a myriad of factors means that our youngsters are not seeing the modeling that is so essential. Instead, all too often, individuals get married without having acquired the basic skills necessary to maintain a healthy marriage. Additionally, they lack the awareness that building a relationship is difficult; it requires time, energy and a strong commitment. It requires understanding that conflict and disagreement are normal in a relationship and they do not mean the marriage is over. Members of the current generation who have grown up with lightning-speed technological advances oftentimes lack the understanding that there is no such thing as instant gratification in a healthy relationship. They come into marriage with an expectation that everything needs to be “good” right away. In my practice, I see more and more couples who have the attitude that marriages that are “hard” can be thrown away, like many disposable things in our society.

Pre-marital workshops are essential. Additionally, every married couple should be expected to have follow-up visits with a mentor for at least six months after the wedding. Skills that need to be taught and practiced include healthy communication, managing finances, renegotiating relationships with families of origin, “fighting” fairly, showing respect, negotiating marital intimacy and a whole host of other topics. Some of these skills can be learned before marriage, but the real work starts after the honeymoon’s over and couples settle down to normal life.

The increase in divorce is also due to an entirely different reason: there is a significant population of young Orthodox individuals who struggle with mental health issues and may be in treatment or on medication. Many families choose to keep these issues a secret for fear of hurting shidduch prospects. While the concern is understandable (and in order for it to change, our community’s approach to mental health disorders needs to shift dramatically), sending a young person into marriage with a “secret” of this sort is often a recipe for disaster. The sense of betrayal that ensues and the damage done to the trust in the relationship are very difficult to repair. Additionally, there are times when such individuals’ functioning is compromised by their condition. When this happens, the other side often pulls out of the marriage very quickly. There needs to be more education in our community about mental health disorders—what they are and what they are not. We can then aim for more honesty in the shidduch process and more reality-based appraisals of whether any given shidduch should take place.

More pre-marital education, more follow-up after marriage and more honesty in the shidduch process, with Hashem’s help, will not only result in fewer divorces, but also in more satisfying, healthy marriages.

Dr. Aviva Biberfeld, Psy.D., has a full time private practice in Brooklyn, New York, where she treats children, adolescents and adults.

Rivkah Rabinowitz

It has become more important than ever to remain connected. So much so that even the formerly insular segments of the frum society have generated a wide range of media forms of their own.

Currently there are daily, weekly and monthly “kosher” newspapers and magazines published and distributed worldwide. Many of them publish well-written articles exposing important social issues and raising communal awareness. Formerly taboo subjects are often openly discussed. Victims are no longer blamed as they may have been in the past. To paraphrase an old advertisement, “We’ve come a long way. . .”

And yet, while the proliferation of such frank discussions in frum media outlets clearly indicates revolutionary growth and thinking, perhaps there is a negative side to all of this as well.

The prevalence of divorce is one such example.

Divorce used to be a taboo topic. When I attended school in the Sixties and Seventies, I did not have a single classmate whose parents had divorced. Out of my high school graduating class of thirty-two girls, one of my classmates divorced early on, and a second after twenty years of marriage.

Out of my twenty-four-year-old daughter’s graduating class of thirty-eight, five classmates have parents who are divorced and there are already four divorces in the class itself. That’s a huge change from my day.

To be a single parent is hard work, no doubt, but it is no longer a source of shame. In fact, there are support groups for frum men and women in that situation and there are shadchanim who specialize in second marriages.

While support groups and other such developments are certainly positive, I cannot help but wonder: were some vulnerable young people influenced by the constant flow of articles on divorce? Were they convinced that their marriages were so bad because they mirrored the stories in certain frum publications where the spouses divorced and then “lived happily ever after”? Did such articles provide a false sense of support and reassurance?

These are tough questions. By bringing issues to the forefront, people are surely helped. But have we contributed to the creation of broken homes? Is all the frum media attention on the tough issues in our society a contributing factor? Does naming the pain, with titles such as “shidduch crisis,” “kids on the fringe,” “abusive spouse” and “Internet addiction,” somehow unleash a monster that feeds on itself? Is the media reporting on a particular phenomenon, or is it in fact helping to create it? This is an age-old dilemma, and the proliferation of frum newspapers, magazines, and other forms of media makes this question more relevant today than ever.

Rivkah Rabinowitz, M.Sc., is a family therapist in private practice. A lecturer of Torah at Chochmas Nashim, she resides in Jerusalem, with her husband, children and grandchildren.

Rabbi Simcha Feuerman

On the one hand, divorce has always been a part of Jewish family life, and for select situations, the best option. However, the sheer number of divorces makes one wonder if all, or even most, could possibly be justified. The potential harm to children, as well as the staggering financial difficulties, makes divorce a serious community concern and not just an act performed by two consenting adults.

One can look at divorce via the following analogy: A person on the verge of divorce is similar to a person who has a severely damaged limb. He could amputate the limb to relieve the pain and stop the infection, but few people would consider this to be a wise option except in the most extreme cases of true life-threatening danger. The same is true for divorce. Unfortunately, however, many people today have an illusion that divorce is a simple procedure and a viable option. It is not. It is an amputation. Furthermore, even actual amputees experience what is known as phantom pain, whereby they feel significant pain where their amputated limbs used to be even years after the limbs have been removed. The Creator may be sending us a message here: It is not simple to remove ourselves from a source of pain. Shortcuts do not necessarily render solutions; the pain continues to haunt us.

It should go without saying that I am not referring to severe situations such as when a spouse is physically abusive toward another spouse or children. Such situations can be best addressed on an individual basis, not in a general article. In any case, there are times when an amputation is warranted.

A person in a seriously troubled relationship may object to the stance taken here. He or she may be thinking: “How dare you suggest I remain married! Am I not entitled to some degree of happiness? Must I be doomed to years of emotional loneliness?” The answer is that of course you have a right to happiness. The question is, will divorce give you the happiness you desire? Unfortunately, life does not give us any guarantees, and happiness may or may not ever come to a person.

What makes matters worse is that our generation’s obsession and constant quest for happiness is, at times, our greatest impediment to achieving a measure of happiness. Our ancestors from prior generations, who coped with relentless poverty and oppression, did not start out their day asking themselves, “Am I happy?” When we constantly question our happiness, we interfere with our ability to embrace and accept the gifts of our present circumstances.

On a more practical level, many people would like to blame their spouses for their misery. “If only he would do this.” “If only she would just . . .” But in almost every situation, each spouse plays a significant role in continuing dysfunctional patterns. Even in situations where one spouse manifests dysfunction in a more obvious manner (such as when one spouse is histrionic, compulsive, depressed, and the like), that is only the surface. The healthy-appearing spouse on a deeper level may be subtly encouraging the other spouse’s dysfunction. Or, perhaps one spouse’s dysfunction may even allow the other spouse to remain stable, by acting out and expressing feelings by proxy. People tend to choose marriage partners who operate on similar emotional and developmental levels. Chazal express this idea as well through the moral lens of mussar: “A man is only matched to a woman based on the quality of his deeds” (Sotah 2a).

The reader should not confuse similarity in emotional development with similarity in personality. Surely on a daily basis we meet couples with many differences. The term “developmental level” has nothing to do with similar personalities. Rather, it refers to one’s ability to manage internal and external conflict, the degree with which one can tolerate intimacy and separation, and the extent to which one can see himself and others, objectively and subjectively. In this regard, couples are remarkably similar, and usually it is the deficiencies in these areas of development that bring about their lack of personal and relationship shalom bayit. This is why divorce doesn’t always bring a solution; people take their problems with them. It is painful but true in many situations: the only way to change others is to change ourselves.

When one is in a failing marriage and the urge is to blame the spouse, it is critical to reverse that kind of thinking, and quickly! Every time you have the urge to blame, even if you are “right,” you must find defects in your personality to correct. In time, you may be surprised with the results. Keep in mind, this is not a guarantee for happiness, but neither is divorce.

Rabbi Simcha Feuerman is a licensed clinical social worker who serves as director of community mental health services for Ohel Bais Ezra. He is also president of Nefesh International, and a clinician in private practice in Brooklyn and Queens specializing in high conflict couples and families.

To hear an interview with Rabbi Feuerman, visit Savitsky Talks at http://www.ou.org/life/relationships/divorce/the-reason-we-get-divorced-audio/ . Savitsky Talks is a weekly twenty-minute audio program exploring topics in Jewish Action and other topics in contemporary Jewish life.

We all know of the dangers of allowing children to have free access to the Internet. What are more subtle challenges that technology poses for the frum home?

Rabbi Dr. Dovid Fox

Technology enhances our lives, no doubt, but as my sainted rebbi, Rabbi Simcha Wasserman, said, it is like the spinning flaming sword outside the gates of Eden (Genesis 3:24). He interpreted that image as symbolizing the double-edged quality of all man-made creations. People invent things that have the potential to be useful, but ultimately, they can be turned around and misused in ways which are harmful. Inside of Eden, God’s creations are purely good. Outside of Eden, in the mortal domain, is “the realm of the spinning sword.” Our technological inventions are two-sided; what could be used to help and protect us can turn and be misused as a weapon to hurt us, be it atomic energy, the laser beam or the computer.

Technology enhances our lives, no doubt, but as my sainted rebbi, Rabbi Simcha Wasserman, said, it is like the spinning flaming sword outside the gates of Eden (Genesis 3:24). He interpreted that image as symbolizing the double-edged quality of all man-made creations. People invent things that have the potential to be useful, but ultimately, they can be turned around and misused in ways which are harmful. Inside of Eden, God’s creations are purely good. Outside of Eden, in the mortal domain, is “the realm of the spinning sword.” Our technological inventions are two-sided; what could be used to help and protect us can turn and be misused as a weapon to hurt us, be it atomic energy, the laser beam or the computer.

The greatest boon of the Internet is that we can get so much more done in so little time. Our taxes, our dissertations, and our letters and correspondence can be amalgamated in moments and sent across the globe in the blink of an eye. Yet the paradox is that the great timesaver also eats up so much of our time. Because we can accomplish so much so quickly, we always make time for a little more online work and this devours whatever hours we might have had for relationships, for proverbial bonding and quality time, and for downtime to reconnect with the human race at a relaxed and introspective level.

Go to a family restaurant and watch the mother, father and children busy on their phones or laptops, no one communicating with each other. Go to a simchah and watch how the people who won’t eat the strawberries are busy with their Blackberrys. This brings the magic of human encounter to a halt; this isolates us further from being able to share ourselves with those from whom we can grow via interaction, and this brings us closer to Asimov than to God. We don’t have “close encounters” anymore. We have closed encounters.

Even in our own internal experiences, technology provides us with rapid access to so much material, yet has anyone davened better, or meditated more clearly or felt more at peace as a result of the picturesque slide shows and PowerPoints which help us visualize better ways to be Jewish? I believe that such technologically enhanced audiovisual presentations are a start for presenting us with inspiration, but integrating such material depends on our learning how to inspire ourselves, not relying on the screen for its momentary arousal. In our rush for shortcuts, we are losing the art of persistence, of concentration, and of learning to solve our problems and questions from within. Technology excites and stimulates our awareness, however briefly, but does not easily impart to us the skills for assimilating data in a meaningful manner.

In times past, one would panic if he left home without his keys or watch. Now we cannot leave home without Internet access to the world, and this dependence on technology limits us from developing the rich and meaningful skills of forming deeper, direct interpersonal connections despite the many benefits that the information superhighway affords us. Perhaps traveling between New York and New Jersey is a suitable metaphor for those of us traveling that “highway” with our technology. When driving from New York to New Jersey, one finds rest stops, tollbooths and state troopers—all of which help monitor the flow and speed of traffic. Similarly, we need some means of slowing ourselves down so that our ubiquitous devices can be stalled long enough for us to connect with our families, with our friends and with ourselves.

Rabbi Dr. Dovid Fox is a forensic and clinical psychologist in Beverly Hills. He gives several weekly shiurim in Gemara and halachah for the Kollel of Los Angeles, and has trained as a dayan with the Rabbanut Yerushalayim. He is a graduate school professor, and also serves as rabbi of the Hashkamah Minyan in Hancock Park.

Rabbi Efrem Goldberg

The proliferation of technology in every aspect of our lives brings with it incredible blessings, opportunities and advantages, but at the same time poses new challenges and difficulties. Many of the challenges are obvious and have been addressed somewhat broadly, such as the easy access and addictive nature of inappropriate and graphic material and images on the Web. Responses and strategies have been offered to combat this particular malady, including installing filters and only allowing Internet access in public spaces within the home.

We would be severely remiss, however, if we didn’t acknowledge some of the other challenges posed by technological progress, many of which are subtle and go unnoticed.

Research shows that smartphones, with their abundance of apps, access to social networking sites and text messaging, are as addictive as drugs and alcohol. The unrelenting urge to check the incoming message or notification has yielded a new phenomenon called “absent presence.” When people are physically in proximity to one another but their minds and attention are elsewhere, in reality they are absent. Couples sharing a meal together but responding to text messages, men checking their e-mail while donned in tallis and tefillin, parents pushing their children on the swings while talking on their cell phones, are all experiencing absent presence.

When Moshe Rabbeinu ascends Har Sinai to receive the Torah, Hashem tells him “alei eili ha’harah, v’heyei sham,” “Ascend toward me on the mountain and be there.” If Moshe is told to go to the top of the mountain, why does he need to be instructed to also be there? If you read between the lines, you can almost hear Hashem saying to Moshe, “I know you are responsible for hundreds of thousands. I am aware that they need your attention and that you are currently occupied with countless responsibilities, but when you come on top of that mountain, put it all aside and be there. Be with Me and Me alone.”

If we are going to experience quality, meaningful time in our relationships, be it with our spouses, our children or with Hashem, we must learn to disconnect. We must rediscover the capacity to be fully present in all that we are doing at any given moment.

There is one relationship in particular in which the pervasive interruption of technology is most destructive and damaging, and that is the relationship we have with ourselves. Real personal growth and progress occur when we have the time and space to think, contemplate and consider. With the explosion of technology, people are less comfortable being alone and experiencing quiet. The constant pings, beeps and alerts create a running background noise in our lives that precludes and prevents silence.

“Vayivaseir Ya’akov levado,” Ya’akov wrestled when he was levado, alone, by himself and without noise or interruption. Our lives are being lived at warp speed, driven by an obsession with technology and leaving us with no time, energy or mental space to wrestle with ourselves, thereby stifling growth and advancement.

Technology excites and stimulates our awareness, however briefly, but does not easily impart to us the skills for assimilating data in a meaningful manner.

The addiction to multimedia gadgets has left an additional casualty in its wake, one that afflicts the younger generation in particular. The ability to daven meaningfully requires the effective use of the imagination and focused vision of the mind’s eye. When we reach out to our Creator praising Him, listing our needs and thanking Him, there is no accompanying music, Youtube video or great app for that. Effective and uplifting davening relies solely on our ability to connect without the help of electronic stimuli and tools. If we and our children are to find meaning in our prayers, we must protect our ability to generate inspiration internally, without the help of gadgets or gimmicks.

Technology has made the world smaller and opened up avenues of communication and connection that were never dreamt possible. And yet, while communication is easier, the quality of our communication is diminishing. Many teens cannot articulate a thought that is longer than 140 characters, the length of a text message. They speak in acronyms such as lol and ttyl. The cell phone bills reveal only a few minutes used but thousands of text messages sent.

Even adults are celebrating major milestones such as semachot, birthdays or anniversaries with a text message greeting rather than a warm phone call. An e-mail or text wishing comfort to a friend who is sitting shivah can never replace the even silent companionship of a personal visit. I heard recently that in dating it has become more popular to break up via text messaging rather than in a dignified person-to-person meeting. Facebook has replaced real face time with real friends and Twitter has supplanted the verbal exchange of ideas.

Technology has given us access to unprecedented amounts of information, but rather than digest it fully, slowly and methodically, we can only read it if it comes in a digest. The trend of reading in snippets, summaries and blogs has infiltrated our Torah learning style as well. Rather than pore over primary sources in all their breadth and depth and subtlety, absorbing their full content, we lean toward seforim and compilations that summarize, condense and present Torah in a manner requiring little thought or exertion on our part.

We must be deeply grateful for the blessing of technological progress. But at the same time we must be vigilant in setting boundaries, creating protocols and being discerning in the technology we embrace and how we relate to it.

Rabbi Efrem Goldberg is rabbi of Boca Raton Synagogue in Florida.

With the rising phenomenon of dual-career families in the Orthodox community, how does the lack of quality time—or just time itself—impact the family?

Rabbi Steven Weil

One of the greatest myths that we all buy into is that quality time can compensate for the lack of quantity time. This is simply untrue. A weeklong trip to Disney World during winter break cannot make up for the dozens of nights when Mom or Dad comes home after 8 p.m. and the kids are already tucked into bed.

Relationships—with our spouses and with our children—must be nurtured. This requires time. It requires patience.

Unfortunately, in contemporary society, time and patience are rare commodities. Spending time with family is especially challenging in this age of distraction. The situation is compounded when parents work full time and come home exhausted and drained, with little energy left to relate to their children. What can be done?

Firstly, try something deceptively simple: start eating dinner together. When I was growing up, it was fairly common for families to sit around the dinner table and discuss current events, the special school assembly, or the upcoming field trip. Nowadays a family that shares a meal together during a weekday is an anomaly—which is nothing less than tragic. When you sit down to eat a meal with your children, you will be amazed at some of things you may find out. The everyday conversations that take place at the dinner table are essential in ensuring your children talk to you about the events, both big and small, going on in their lives. Eating dinner together is not simply a gastronomical experience; it is an emotional experience that helps form the glue of family unity.

Secondly, make Shabbat a day devoted to family. All too often parents spend the Shabbat meal entertaining other adults while the kids leave the Shabbat table shortly after Kiddush to play a game of Monopoly. This is not what Shabbat should be about. Shabbat is an ideal time for working parents—indeed for all parents—to reconnect with their children. There is no substitute for solid blocks of unrushed, unscheduled family time. On Shabbat, there is no train to catch, no carpool to arrange. Take the time to play a game of Chutes and Ladders with your four-year-old or build a Lego police station with your eight-year-old. On Shabbat, don’t only socialize with your adult friends; socialize with your children. Your friends may or may not remember spending Shabbat afternoons with you. Your children will always remember it.

Thirdly, if you find that the pace of your life is truly impinging on your and your family’s emotional well-being, you can make a sweeping life change—move to a community outside of New York. You will pay significantly less money for a house and without the crushing financial burdens of living in a large city, you might find that you are working less and enjoying your children more.

Rabbi Steven Weil is executive vice president of the Orthodox Union.

How can we instill derech eretz and respect in our children? How do we imbue our children with strong religious values in today’s irreligious, irreverent age?

Rabbi Dr. Dovid Fox

Derech eretz is difficult to define. Our sages tell us that Yitro petitioned his son-in-law Moshe Rabbeinu to be sure to include derech eretz among the values which Jews must embody. Derech eretz, according to our tradition, includes aspects of conduct which show concern for others in speech, in deed and in thought. It is difficult to formally command someone to have or display derech eretz, yet it is an area which extends from and is derived from the general rule to love thy neighbor, the famous “klal gadol” or governing principle of so many of our religious standards and interpersonal practices.

We model this value by acting with derech eretz ourselves, but we also need to teach derech eretz by talking about it with our children. We should encourage children to look at great Biblical and Talmudic figures, as well as contemporary exemplars and even characters in the acceptable books they read. Then we must challenge our children to spot and describe the value that is demonstrated, the inspiring lesson one can learn from the figure or character. It may be the value of consistency, or compassion, or generosity or of finding creative solutions to difficult problems. We want our children to search for the value, to share it with us (or if they are younger, we want to teach them how to look for the good in others and then experiment with emulating their goodness), and then we want to challenge them to understand how they might practice living with a similar standard.

We need to scrutinize our children’s reasoning. A youngster can read a story and derive the wrong lesson from it. Our job is to guide their thinking, expand the limits of their moral awareness, and depending on their maturity and developmental level, challenge them further to research that middah or quality by studying about it. We can only expect a child to take on a quality if it is personalized. Keeping a moral lesson cerebral, limiting it to book learning or to an academic format, will not help a student assimilate the lesson on a meaningful level. Shlomo Hamelech uses the term “mussar haskel” which is probably best understood as a “moving lesson” or an enlightening realization. We can only move our children and students if we successfully convey that a quality is doable, valuable, and relevant to them, and that it will help make them more complete human beings.

Lastly, derech eretz is as its name implies: it is what people do. That means that we must do it as well. If we expect our young ones to develop decency and consideration for others including for us as parents, we have to do “what people do” ourselves. I see fathers bringing their young sons to shul on Sunday mornings. They plop the children down with the latest colorful illustrated siddurim, point to the page the children are supposed to be saying if they want a mitzvah note sent to their teachers, and the dads proceed to text their way through Shacharit or converse with their friends. Derech eretz begins with us.

Shana Yocheved Schacter

Mr. B has been in therapy since he lost his job a year ago. This particular day we speak of his teenage children. They have been drifting away from the home more than usual lately, and seem to be cutting corners in their religious observances rather than engaging in them with any emotion or sense of purpose. The spark is clearly missing from their religious lives, and their parents are at a loss as to how to re-engage them. Mr. B. blames their teachers for being sub-par, evidenced in the growing alienation of his children to all things spiritual.

This scenario is a familiar one, even while the details may differ from teen to teen.

The same boy or girl who can be excited about the newest tech-gadget, fashion item or vacation plan is left cold when davening. How can she or he become interested in spirituality and motivated to care about involvement in ritual and communal life? What is the secret to inspiring our children and preventing feelings of indifference toward, or worse, disdain for, all things authoritative and religious?

Real personal growth and progress occur when we have the time and space to think, contemplate and consider.

There is no magical answer to this age-old dilemma of how to reach adolescents about anything at all. However, my experience has shown that parents who take direct responsibility for instilling values in their children will meet with far greater success than those who are reluctant to do so. What are parents to do?

Communicate clear expectations to children. Boundaries and limits that you set for your children of all ages create a framework within which your children can experience the world as a predictable and safe place. It is your responsibility to discuss goals and strategies for schoolwork as well as to convey a serious interest in your teens’ social plans (what, where and with whom).

Have honest conversations with your children. Such discussions result in trusting and lasting relationships. Whether struggling with theological matters (illness and death), sociological or political issues (the future of the Jewish people in America, Israel and around the world), ethical issues (world hunger, war and peace, abuse and famine), or more personal concerns (friendship, dating, anxiety, or body image), your active participation in these challenging conversations is invaluable. Often, the questions raised are better than the answers. However, it is reassuring for teens to know that you also struggle and are not insensitive or uncaring.

Demonstrate derech eretz. Take your children’s doubts and struggles seriously rather than argue them away. Look for opportunities to have these conversations while doing random errands, while sitting around the Shabbat table or while on vacation. Simply talking to your children in a thoughtful and respectful manner is the best way to present your positions as well as to defend against cynicism and disrespect for you and your values. There is no place for self-righteous and condescending language that only reflects your weaker, insecure self. Do not strive to be right. When your children feel they are being heard (though not necessarily agreed with), they will be more open to considering another point of view.

Teens are also particularly alert to inconsistencies in adult behavior, are sticklers for fairness and may have trouble grasping nuanced issues that are not black and white. Providing the space at home and in school to articulate concerns and feelings (anger, fear, excitement, confusion, et cetera) can neutralize their negativity and offer an opportunity for you and your children to process and reflect on them together.

Spirituality will thrive when a respectful climate exists. A climate of respect between adults and children is achieved through ongoing communication. Reclaim your role as parent and model derech eretz for your children.

Shana Yocheved Schacter, certified social worker, is a psychotherapist and psychoanalyst in private practice on the Upper West Side of Manhattan and in Teaneck, New Jersey.

How does the emphasis on materialism and “keeping up with the Joneses” mentality affect our children as well as our marriages?

Rabbi Steven Weil

In the aftermath of the rioting in London this past August, Chief Rabbi Lord Jonathan Sacks wrote a penetrating article in which he blamed the lawlessness on rampant consumerism.

But what we have witnessed is a real, deep-seated and frightening failure of morality. These were not rebels with or without a cause. They were mostly bored teenagers, setting fire to cars for fun and looting shops for clothes, shoes, electronic gadgets and flat screen televisions. If that is not an indictment of the consumer society, what is?

Indeed, we live in a world where whether we like it or not, we absorb the values of Madison Avenue. And what is Madison Avenue telling us? The goal of all advertising is to convince people that their wants are truly their needs. It is to manipulate them so that they believe that with this one purchase, their lives will be vastly and dramatically improved—which is, of course, a great lie. Our deepest needs are not material; they are emotional, they are intellectual, they are spiritual. Our grandparents and certainly our great-grandparents did not go on skiing vacations during winter break. Many of us take two or more family vacations each year. But does this make us any happier overall? Do we live more fulfilled, actualized, satisfied lives because we have been to Disney World?

If our whole focus in life is on amassing more and more material things and on keeping up with our neighbors, we are resigning ourselves to lives of frustration. Material acquisition is a goal that can never be fully realized.

Your house may be quite large, but when your neighbor extends his house by twenty-five feet, suddenly your house begins to feel cramped. One’s material desires can never be truly satiated; it’s like pouring water into a bucket with a hole at the bottom.

On a deeper level, we need to ask ourselves some serious questions: is materialism the overriding value we want to convey to our children? Should we really be discussing kitchen renovations and the latest pattern in bathroom tiles at the Shabbat table? Do we really want our children to see us investing significant emotional and psychological energy into purchasing new window treatments?

If these are not the values and ideals we want to pass on to our children, then we must reevaluate our way of life and our attachment to the superficial. We must make a decision to invest as much energy into our relationships and into our intellectual and Torah pursuits as we do our material pursuits. We must redirect and rechannel our kochot. We must redefine for ourselves what are truly needs and what are wants. We cannot afford to let Madison Avenue make these critical decisions for us.

Most of us know at least one family with an off-the-derech child; what is the impact of this phenomenon on the siblings? On the family?

Rabbi Ilan Feldman

The questions posed in this symposium relate to developments in our community that, at best, are to be weathered or survived. The questions boil down to this: we are confronted by realities we cannot change, what can we do to minimize their negative impact on our community, or somehow survive them?

There is, however, one painful development referenced in these questions that has the potential to bring a lasting and positive dimension to Orthodox living. I refer to the question regarding off-the-derech children and the effect this disturbingly common phenomenon might have on us. Paradoxically, in this case, the illness will provide its own antidote.

A variety of ingredients converge in the life of a young person to form the perfect storm that blows him “off the road.” Though each case has its unique array of factors, it is safe to posit that the phenomenon represents not an intellectual breakdown as much as a sociological breakdown.

One of the greatest myths that we all buy into is that quality time can compensate for the lack of quantity time. This is simply untrue.

Talk to young adults who were raised Orthodox and who are no longer observant and one often hears a recurring complaint that played a key role in these cases: the subtle, unstated but implicit and powerful expectation that a child follow a certain path, or else. What is insidious about this factor is that it makes no difference if a particular set of parents or series of rebbeim did not subscribe to this attitude, or even if they verbally profess acceptance of a certain level of deviance from the mold. What matters is that the community as a whole sent a message to the developing Jew. That message almost invariably is, “the way we live is the only right way, and if you don’t share our view, you don’t belong here.” The problem is that the child believes both halves of the “sentence”—other ways are all wrong, and since I wish to explore other models, I don’t belong here either.

Where is this message expressed? From the pulpit, in the classroom, at the Shabbat table, in the yeshivah. By nature, a discussion about lifestyle and mission, meaning and purpose, right and wrong, almost inevitably requires the authority figure to justify his or her position in comparison to other positions. Each group must rationalize its existence; in doing so, it is so easy to fall into the predictable trap of condemning others. Why do/don’t our children serve in the Israeli Army? Why do/don’t we subscribe to Torah U’madda? Only the most disciplined, tolerant, secure, and loving authority figure will explain the answer while leaving room for, even respecting, an opposing view.

Few Orthodox communities feel competition for the hearts and minds of their children from Reform or Conservative Judaism. But mention Modern Orthodoxy’s approach to Israel at a Yeshivish table, or Lakewood’s position on smartphones at a Modern Orthodox table, and you will inevitably observe examples of fear and defensiveness masquerading as intellectual thoughtfulness. The result of these conversations, repeated ad infinitum in formal and informal discussions throughout one’s teenage years, is a fundamentalist, judgmental, narrow-minded religious world filled with angry, uninspired, indignant adults. Inspiration as a rhetorical and pedagogical tool is rarely practiced. Left with the choice of conformity for the sake of satisfying communal norms or being wrong and stupid by following another approach, young people are asphyxiated. It is a wonder more don’t opt out.

We believe in Torat Emet, in Olam Haba, in serious and eternal consequences of a non-Torah life. The phenomenon of off-the-derech children is heartrending. But I am hopeful that having to deal with off-the-derech people in our lives—children, siblings, uncles and aunts, people we love and a phenomenon closer to ubiquitous than to occasional—is going to be a growth experience for our community. Parents, siblings, rabbis, teachers are going to learn to love while disagreeing, to see personal virtues even in someone who doesn’t follow halachah, and to make room in their lives for people whose existence requires a subtle combination of intellectual rigor and emotional sensitivity. Dismissive, simplistic clichés of religious rhetoric and self-justification won’t work anymore. What will necessarily develop is a sophisticated worldview which forces the frum world to abandon condemnation of the other in favor of invitations to inspiration as the major tool for influencing others. That would be refreshing, but even more significantly, it would put the frum world back on the derech.

Rabbi Ilan Feldman has been the rabbi of Congregation Beth Jacob in Atlanta, Georgia, since 1991.