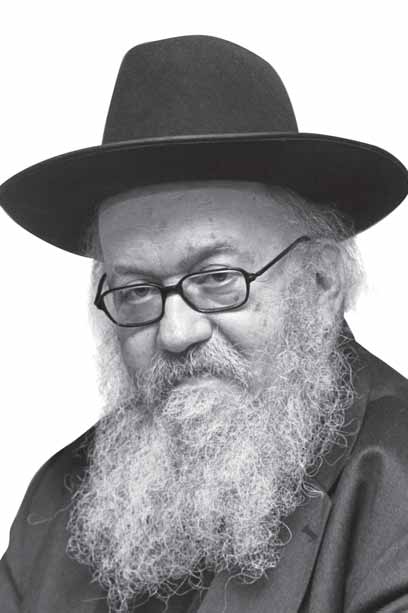

Editor’s Note: The Chief, a new book about Rabbi Chaim Goldzweig, was recently released and can be purchased online. The book details the enormous contribution Rabbi Goldzweig, who passed away in 2018, made to the OU and to the world of kashrus. Below is a tribute we ran in 2011, marking Rabbi Goldzweig’s fiftieth anniversary with the OU.

Before PCs, iPads and iPods, there was Rabbi Chaim Goldzweig. An Orthodox Union rabbinic field representative who recently marked his fiftieth anniversary with the OU, Rabbi Goldzweig is known in food manufacturing plants across the globe as the OU’s walking, talking kosher database.

In 1960, when Rabbi Goldzweig first joined the OU’s kosher division, known today as “OU Kosher,” it was a fledgling operation with just a handful of full-time mashgichim in the field. At the time, the world of kosher certification was in its infancy.

“As long as the ingredients panel didn’t list lard, everybody thought it was fine,” says Rabbi Goldzweig, who lives in Chicago.

Intent on learning everything there was to know about ingredients, Rabbi Goldzweig quickly became the “go-to” ingredient maven, with four phone lines to accommodate the daily deluge of calls he would receive from kosher agencies and consumers around the world.

“He could walk into a plant and just by looking at the code on an ingredient container, he would know exactly who manufactured it and if it was kosher,” says Rabbi Moshe Elefant, COO of OU Kosher, which today boasts a high-tech database with nearly 350,000 kosher food ingredients.

An OU mashgiach inspects equipment at a New Jersey beverage bottling plant.

“Companies feel safe with him. They trust him,” says one OU RC. “In the final analysis, kosher is very much a function of trust. You’re not going to entrust a major part of your multi-million dollar business to someone you don’t trust.”

Rabbi Goldzweig engendered such confidence that an oil company in India insisted that he—and only he—be in charge of overseeing its kosher production, which would require him to spend the year in the country. Rabbi Goldzweig explained that he couldn’t possibly stay away from his family for so long. “The company spent over one million dollars on his airfare just so that he could fly home for Shabbat and be back [in India] on Monday,” says an OU RC. “It was based purely on the personal relationship.”

Crisco, a shortening made entirely of vegetable oil instead of lard, was invented in 1910. Three years after the product was on the market, Proctor & Gamble began advertising that Crisco was a cheap and kosher product for which the “Hebrew Race has been waiting 4,000 years.” In 1985, Crisco became OU certified. Courtesy of the J.M. Smucker Company Corporate Archives

His disarming manner put people at ease. “He’d walk into a plant looking like the TV-detective Columbo, wearing an old hat and a disheveled jacket with overstuffed pockets, where he kept all his notes and pieces of paper,” says Rabbi Michael Morris, an OU RC.

Rabbi Goldzweig, his colleagues say, would act as if he didn’t know much. In short order, company executives would realize that he knew more about their production than the technical people in the company.

Globetrotting for Kashrut

Rabbi Goldzweig’s entry into the kashrut field began when the OU hired him as a rabbinic field representative (RFR) for Procter & Gamble. Soon the OU began sending him to plants around the world. Every Sunday morning, he would call the supervising RC to plan his itinerary for the week. By Sunday evening, he was bound for somewhere in the US, or in Europe or the Far East.

“I have more stamps on my passport than Carter has liver pills,” says Rabbi Goldzweig. Along the way, OU Kosher’s Columbo amassed many memorable episodes—some funny, some moving and others downright scary.

Once, after landing in Malaysia, Rabbi Goldzweig was approached by two men sporting rifles and bayonets. They asked if he was Jewish. Although nervous, he kept his wits about him. “Let’s see . . . I’m not Irish,” he told them. “I’m not Polish, Swedish, Greek . . . I think I must be Jewish.” Not amused, they asked him what he was doing there. “You know I’m beginning to wonder that myself,” he said. “If you don’t want me here, I don’t mind going back on the next plane ’cause you guys paid for the tickets.” He pulled out a letter from Procter & Gamble confirming his supervision of a vegetable glycerin run. They let him go.

An OU mashgiach makes the rounds.

His winsome disposition not only got him out of jams, it also inspired lifelong friendships. One of the managers at Procter & Gamble sued his ex-wife for custody of their children. He asked Rabbi Goldzweig if he would be a character witness. Rabbi Goldzweig agreed. “The judge was trying to surmise why in the world they called in a rabbi,” says Rabbi Goldzweig. “He asked me how I knew the man. I explained that I worked at Procter & Gamble as a kosher supervisor and that I’d been to his home and knew his family. He asked me some questions about kashrut then banged his gavel and announced that because the manager got a rabbi to be a character witness, he’s going to give him the children. I can’t tell you how happy he was.”

The Mashgiach’s Mashgiach

The string of RCs under Rabbi Goldzweig’s tutelage still consider him the king of kashrut. “There is no bigger boki [expert] in the field—then and today,” says Rabbi Dovid Jenkins, OU RC. “He taught me how to go through a facility, how to look at ingredients, how to decipher which are problematic or not—all in clear, understandable terms.”

He also transmitted the tricks of the trade. “He was famous for using the ‘salami method,’”says Rabbi Juravel. “He’d walk into a plant with several kosher salamis in his pockets and give them out as presents. The workers became his best friends.”

The plant managers were also smitten. “He is one smart person,” says Ray Henry, retired president and CEO of Daddy Ray’s, the country’s largest manufacturer of fig and fruit bars. “He is bubbly and friendly and probably the only guy who would let me hug him.”

Rabbi Goldzweig approached the plants’ kosher glitches in the same gracious manner. “He never looked down on anyone; he treated them as equals,” says Rabbi Mordechai Grunberg, an OU RFR. “Once, we were sitting at an initial meeting with the plant administration, and Rabbi Goldzweig was trying to get information on a certain raw material. He suspected that it could be animal based. In a nice way, he asked if . . . they were sure they had all the ingredients listed. He suggested they review it again. He knew that the raw material had to be there.”

Once the executives realized that the rabbi knew exactly which ingredients should be in the particular product, and that they weren’t going to get away with hiding anything, they came clean. “Mostly, they appreciated how he let them know in such a polite indirectly direct way,” says Rabbi Grunberg. Word got out in the industry that when Rabbi Goldzweig comes to a plant, give him everything, because he’s going to help you; if you can’t get a raw material from a kosher source, he has another source in his left shirt pocket, and he’ll make a call for you on the spot.

Although his kashrut work took him away from home for most of the week, it didn’t detract from his devotion to family. “Except for the times he had to fly to Hawaii to supervise macadamia nuts, he never missed a Shabbos at home,” says his daughter, Beila Lichter.

“There’s no question that Rabbi Goldzweig was a pivotal player in the development of kashrut in America. He was the OU.”

Growing up, the Goldzweig children couldn’t help but notice that their father was an important person in the community. “Wherever we went, people stopped to ask him questions about products and ingredients,” says his son, Pinchus. “Whenever we went to food stores, he would walk around looking at ingredients. Once, while in a supermarket, he picked up a certain product, and a woman came running over, saying: ‘Rabbi Goldzweig said you’re not supposed to use that item!’ He quickly put it down and went to the next aisle, where another shopper approached him with a question, addressing my father by name. The first woman overheard and apologized. He said: ‘At least I know people are listening to me.’”

Today, OU RCs continue to call him for advice. “I still need to hear his judgment on an issue,” says Rabbi Paretzky. “I also encourage members of the new kashrut staff who haven’t heard of him to call Rabbi Goldzweig. Besides, the man is a real upper. If you’re ever in a bad mood, call Rabbi Goldzweig; you’ll be in a good mood within five minutes.”

“The kashrut department was built on his shoulders,” says Rabbi Menachem Genack, CEO of OU Kosher. “He is a man of commitment, knowledge and concern for every aspect of the job. He is what we call the ‘super mashgiach.’”

Bayla Sheva Brenner is senior writer in the OU Communications and Marketing Department.