A moving tribute to the Bostoner Rebbe, on his first yahrtzeit (1921-2009).

A moving tribute to the Bostoner Rebbe, on his first yahrtzeit (1921-2009).

A very long and productive life came to an end last December—long not just because the Bostoner Rebbe died at the age of eighty-eight (18 Kislev 5770), but because of what he packed into each day.

The Rebbe, Rabbi Levi Yitzchak Horowitz, occupied a unique place in Jewish life. A Boston-raised American steeped in the accent and the habits of New England, a Meah Shearim-educated Torah student immersed in the ways of the pre-Zionist Orthodox community in the Holy Land, a self-educated medical expert about whom a Harvard professor of cardiology said, “the Rebbe has earned his MD by default,” a staunch proponent of traditional Jewish life, a beloved figure among countless physicians and secular Jews . . . a . . . a . . . the paradoxes mount and a complete picture of the Rebbe becomes impossible. We might sum up his life this way: He was the ultimate bridge builder.

This meant people—people in his home. People in his study. People at his Shabbat table. Week in and week out, year in and year out, the Rebbe and his unforgettable helpmate, Rebbetzin Raichel, hosted twenty to forty people each Shabbat. They bought a house with many floors just to be able to host all these people for Shabbat—and to host charity collectors, medical patients, passers-through. All were welcome in their home and with each one the Rebbe built a bridge. The high and the mighty came—the politicians and the eminent Torah scholars—as did the lowly and the downtrodden. With each one, without distinction, the Rebbe built a bridge.

The Rebbe had no formula for reaching out and touching people. He spoke very well, but he davened even better than he spoke and touched many people through the example of his prayers. It was inspiring beyond measure to listen to the Rebbe daven, especially on the Yamim Noraim, Rosh Chodesh and Shabbat. That way, too, he built bridges—not only between himself and people, but more so, between people and their Creator.

A typical Shabbat table at the Rebbe’s might find a couple of students from MIT or Harvard with no knowledge of Hebrew or Jewish practices, a visiting Torah scholar from Jerusalem decked out in traditional black kapota and hat, a couple linked by the Rebbe to Boston medical centers for fertility treatment, a family from the community, . . . and. . . a writer for. . . the New Yorker checking out the scene.

Mainly, though, the Rebbe reached people through his intuition. He grasped people instantly and saw through the issue that was presented to the real one. He had a way of being clear and being subtle, of being lofty and wise, and down-to-earth and direct, all at once. This personal capacity aided him especially in reaching out to college students. A typical Shabbat table at the Rebbe’s might find a couple of students from MIT or Harvard with no knowledge of Hebrew or Jewish practices, a visiting Torah scholar from Jerusalem decked out in traditional black kapota and hat, a couple linked by the Rebbe to Boston medical centers for fertility treatment, a family from the community, a charity collector from New York and, from time to time, a writer for the Boston Globe, Jewish Advocate or New Yorker checking out the scene.

The Rebbe ducked no issue and no personal problem. Whatever came his way he embraced, no matter the personal price in time, angst or money. One couple’s marriage was in trouble, another person’s child had a potentially fatal heart defect and a third person’s livelihood had collapsed. If a single word animated the Rebbe’s approach, it would be responsibility.

Never was this clearer than in the last twenty years or so of the Rebbe’s life when he suffered severe heart ailments. They would have felled a lesser person, who would have had ample reason to beg off any further involvement in other people’s lives. Somehow, even after his first rebbetzin passed away, the Rebbe’s Shabbat table remained full; the scores of congratulations letters to new brides and grooms—personally signed—still went out. Most amazing of all, until the last year or two of his life, the Rebbe still commuted between Boston and Jerusalem, so that he could minister to his flocks on each continent.

Responsibility: As the flow of college students tapered off somewhat at the end of the 1970s, the Rebbe did not relax. He redoubled his efforts on behalf of the ill through ROFEH (Reaching Out, Furnishing Emergency Healthcare). He and his rebbetzin had always taken in the sick, but now he hired a staff and raised funds to buy apartments so that more people, for longer periods of time, could afford to stay in Boston to receive medical treatment.

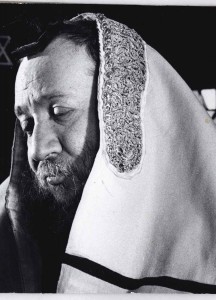

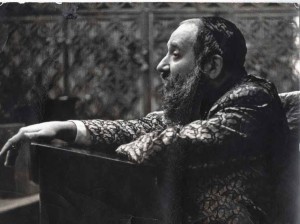

The Bostoner Rebbe, Rabbi Levi Yitzchak Horowitz, 1921-2009

The Bostoner Rebbe, Rabbi Levi Yitzchak Horowitz, 1921-2009

Photos: Joel Orent

He galvanized volunteers—this one, a driver, that one, a translator, another one, a medical contact person. This free service was (and remains) for Jews, observant and non-observant, as well as for non-Jews. The mitzvah is to save a life, anybody’s life, the Rebbe said.

The Rebbe accomplished all this while remaining true to his beliefs and his traditions. Chassidic life generally calls for a very strict level of observance, and the Rebbe sustained this with the same zest that he put into helping college students and the medically needy. The Rebbe remained active in Agudath Israel of America—this was his ideology—even as he had a way of speaking to Jewish leaders across the religious spectrum. When he first began his community in Jerusalem in 1984, he became the only Orthodox Jewish religious leader in the city to enjoy a genuine friendship with the city’s mayor, Teddy Kollek.

When my wife and I brought the Rebbe to Denver in 1987 for a multifaceted visit and Shabbaton, he spoke to the leadership of the Allied Jewish Federation and to the medical personnel at a local Catholic hospital, St. Joseph. The Rebbe davened at a Modern Orthodox shul and a Chassidic shul. He also spoke at a melavah malkah at the Lakewood-affiliated yeshivah, Toras Chaim. All were touched and uplifted. The Rebbe was the ultimate bridge builder.

The Rebbe left behind long lines of children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren, in the United States and Israel, as well as institutions that carry on his legacy. Each of his three sons has become the Bostoner Rebbe, one in Boston, one in Jerusalem, and one in Boro Park. In his spirit and in his aftermath, there are no struggles over succession. Mostly, however, the Rebbe left behind thousands of people in tears, grieving his loss, confounded and bereft. Above all, the Rebbe was a father and missing is his unique voice, his capacity for friendship, his penetrating counsel, his illumination during the personal darkness in which all of us sometimes find ourselves. Never shall we see his like again—but, we may at least hope, we have gained and grown from his example and can share at least something of his spirit with others.

Rabbi Hillel Goldberg, executive editor of the Intermountain Jewish News, is a contributing editor of Jewish Action.