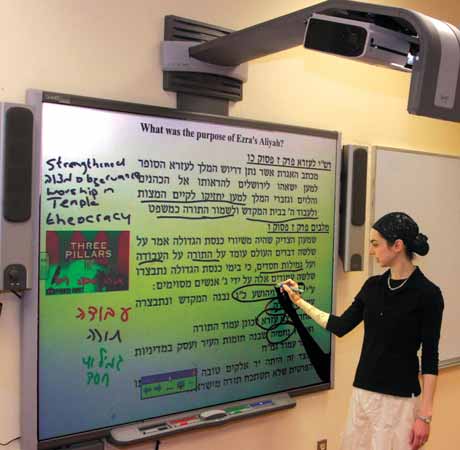

Technology in the Classroom

At The Frisch School, a teacher uses a Smart Board to teach a Navi class. Courtesy of Rabbi Tzvi Pittinsky

There is no question that technology can transform–and in some schools already is transforming–Jewish education.

Teachers often bemoan the fact that students who have been in yeshivah their entire lives often have difficulty deciphering a pasuk in Chumash. However, while all teachers agree that Hebrew reading skills are important, they rarely devote significant class time—especially in high school—to this important skill. The reason is simple. Teaching reading is boring and time-consuming. In the traditional yeshivah environment, where many hours are devoted to chavruta-style learning, perfecting reading skills in the majority of students may be an achievable goal. However, in a typical Jewish day school where classroom instruction is divided into forty-minute periods, teachers cannot spend time calling upon multiple readers without tuning out the rest of the class.

Enter Voicethread. Voicethread (www.voicethread.com) is a free web-based application that allows one to record himself without using any special software. The teacher can post a piece of text and assign students to read it for homework. The student then logs in and, using a computer and a microphone (virtually every laptop today comes with a built-in microphone), the student reads the text back to the teacher. The teacher can then grade each student individually on his or her reading, even on a nightly basis, without taking a moment of class time.

What’s a Wiki?

Wiki is another great example of how web technology can be used in the classroom. Hawaiian for quick, wiki lives up to its name as a fast and easy way to create web sites that allow users to add and update content. The most famous example of a wiki is Wikipedia, the online encyclopedia collaboratively created by thousands of volunteer contributors. At The Frisch School, where I serve as the director of educational technology, we use Wikispaces (www.wikispaces.com) to create wikis for each grade level focused around a common theme. The goal is to tear down the classroom walls by fostering collaboration between different classes. Pages are edited by multiple teachers who post content from various classes related to the particular theme. Therefore, a typical page can have material posted from Chumash, Navi, English and science classes.

Online discussions are more than just homework assignments; they are valuable forums for students to flesh out their ideas about religion and life.

Students interact with the wiki primarily through discussion forums included on each page. These forums promote student reflection, participation, and interaction. In a typical classroom discussion, students have little time to reflect. Many thoughtful students who require more time to process information are sometimes left out of classroom discussions. In an online discussion, however, students can think over a question before composing a carefully crafted response. Some of the most profound responses have come from students who rarely speak up in class. Such online discussions are more than just homework assignments; they are valuable forums for students to flesh out their ideas about religion and life in a safe educational setting.

Students at the Rosenbaum Yeshiva of North Jersey

Photo: Judah Harris

Gemara Simplified

Technology also creates exciting opportunities for “constructivist learning,” that is, when students, instead of passively listening to information from teachers, construct meaning on their own through their interaction with the text. This kind of learning takes place in advanced yeshivot. However, in the typical Jewish day school, students often lack the skills necessary to learn on their own. With the aid of technology, students can become independent learners.

Take the program Gemara Berura (www.gemaraberura.com), for example. A powerful tool that helps students “make a laining” or read a gemara on their own, Gemara Berura divides a discussion in the gemara into segments, classifies the segments according to their function and connects the units of shakla vetarya (the questions and answers of the gemara) to each other. The program uses a special system of color-coding and shapes to represent different elements of the debate.

For the more creative teacher, the ability to incorporate text, images, video, and interactive maps transforms the entire lesson.

For example, a unit in a gemara can be a statement, a question or an answer. Questions and answers can be classified even further. Is the gemara merely asking a question of information, is it making an inquiry, or is it offering a rebuttal? Gemara Berura enables the student to generate graphic representations of the gemara text, helping him to better understand the sugya.

It is important to note that the program does not make learning Gemara into a game where the “wrong” answer is accompanied by a bell or whistle. It is open-ended, allowing the teacher and student to choose how to understand the sugya.

What’s So Smart about a SmartBoard?

The Smart Board is also changing the way Judaic studies, especially textually intensive subjects like Gemara and Tanach, is being taught in day schools and yeshivot across the country. (Schools have obtained Smart Boards either through government funding or from grants from Jewish organizations such as the Legacy Heritage Foundation Smart Board Project and the Gruss Foundation’s Center for Initiatives in Jewish Education.) What is a Smart Board?

Providing the simplicity of a white board with the power of a computer, a Smart Board is a giant touch screen where one can manipulate items projected from a computer to the front of the classroom. Interactive whiteboards are user friendly and enable teachers to incorporate more digital and interactive resources into their lessons.

On the most basic level, a Smart Board allows one to project text from the Talmud and Tanach in the original tzurat hadaf, drawing from web sites such as http://e-daf.org, http://hebrewbooks.org/shas, http://mechon-mamre.org or the Bar-Ilan Responsa Project. One can easily highlight text on a Smart Board to help identify shorashim, the steps in the shakla vetarya of the Gemara, or key ideas in the commentaries. For the more creative teacher, the ability to incorporate text, images, video, and interactive maps transforms the entire lesson. Because the teacher is manipulating all of this from the front of the room, the lesson can flow seamlessly through the different modalities.

Teaching the earthquakes and total eclipses of the sun, for example, in the Books of Amos and Isaiah with the use of a Smart Board could be very compelling. The teacher can first present the various verses indicating these phenomena on the Smart Board and the major commentaries on them. Many commentaries maintain that the earthquake predicted by the Prophet Amos is the same one described in Isaiah’s inaugural vision (Isaiah 6), which occurred as a result of King Uzziah’s attempt to act as a High Priest and bring incense into the Temple (2 Chronicles 26). King Uzziah’s act led to both personal and national calamity. On a personal level, King Uzziah was stricken with leprosy. This can be illustrated on the Smart Board by showing the students the Rembrandt painting King Uzziah with Leprosy. On a national level, the entire Israel and Judea suffered a massive earthquake. Students can be shown archaeological evidence of the major earthquake that took place during the first half of the eighth century, during the time of King Uzziah, from digs in Hazor and other Israeli cities.

The teacher could also discuss the prediction of a total eclipse of the sun which figures prominently in the Book of Amos (for example, see 8:9; 4:13; and 5:8-10) and also appears in Isaiah (13:9-10). Once again, archaeological evidence of the total eclipse of the sun can be presented based on the Assyrian Eponym List, dating the event precisely to June 15, 763 BCE, the only total solar eclipse to occur over the Middle East in a 1,000-year span. Evidence from astronomy can also be used to verify this event. With the help of a special Google Earth file featured on a NASA web site (http://eclipse.gsfc.nasa.gov/eclipse.html), the teacher can take the students back in time to June 15, 763 BCE. Using a Smart Board, the students can move the globe with their fingers to the Middle East and zoom into any location to show the exact time the eclipse was seen over Israel (between 8:11 AM -10:54 AM, Israel time) and the percentage of the sun that was covered in the eclipse (a total eclipse over Assyria, over 90 percent eclipse over Israel). By using technology, the teacher can demonstrate these events from both archaeology and astronomy and further students’ appreciation of and emunah in Tanach. Many more examples of Judaic studies lessons designed to harness the power of the Smart Board can be found on the Legacy Heritage Foundation Smart Board Jewish Educational Database at http://www.legacyheritage.org/SJED.

As the technologies described above become even more common, affordable, and user-friendly, and as new technologies are applied to education, the array of tools available for the Judaic studies teacher will continue to increase. With the help of talented teachers, curriculum specialists, and administrators, these technologies can be effectively used to engage students and strengthen limud Torah.

Rabbi Tzvi Pittinsky is the director of educational technology at The Frisch School in Paramus, New Jersey. He writes a popular blog on technology and Jewish education at http://techrav.blogspot.com